“Every child is an artist. The problem is how to remain an artist once he grows up.” (Pablo Picasso)

“Just think of the tragedy of teaching children not to doubt.” (Clarence Darrow)

In America, the concepts of work and career infiltrate just about every aspect of our lives — usually to our detriment. Consider the most common question we’re asked from the time we’re old enough to understand it: What are you gonna be when you grow up?

The assumption in this inevitable question, of course, is that the child being quizzed isn’t exactly “something” yet. Thus, the expected answers fall within a range of “somethings” like a cop, fireman, ballerina, president, doctor, astronaut, princess, etc.

It would be jolting if a seven-year-old were to reply with a far more likely “something” like a cafeteria worker, actuary, or manager at Staples.

It would be almost as jolting if a career counselor at an Ivy League school were to hear a student say something like this: “I don’t wanna work in finance, law, advertising, or anything corporate. I wanna be an artist and activist.”

This scenario was the premise for my second book way back in 2002 and for Yale University inviting me to speak there in 2003.

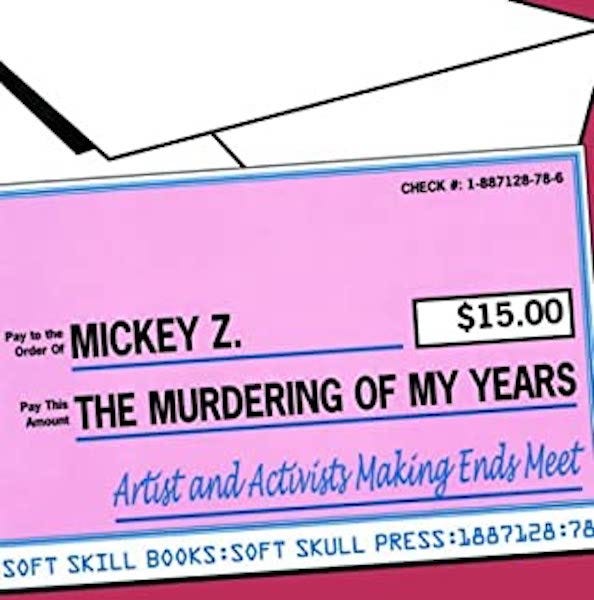

In my book, The Murdering of My Years: Artists and Activists Making Ends Meet, I interviewed a diverse group of fringe characters about how they balanced their personal vision with the demands of a capitalist culture.

Somehow, the book ended up in the hands of a woman who ran the career counseling department at Yale. It seems they had a huge convention coming up at which career counselors from all the Ivy League schools would gather.

This group knew their field well — with one admitted blind spot. They didn’t know how to handle young folks who were not following the expected path of a student at an elite university.

That’s where yours truly came in. I would be paid to serve as the keynote speaker in the name of connecting the suites with the streets. I began that lecture like this:

“Today is the 102nd birthday of Werner Heisenberg, the German physicist who won the Nobel Prize in 1932 for discovering the uncertainty principle. Simply stated, good ol’ Werner found that it is physically impossible to measure both the exact position and the exact momentum of a particle at the same time. In other words, the more precisely one of the quantities is measured, the less precisely the other is known. Replace the word ‘particle’ with the word ‘student’ and Mr. Heisenberg just may have summed up the life of a career counselor.”

Having clarified that they were in for something different, I introduced the “whaddya wanna be when you grow up?” contemplation. The schoolboy version of me, if he could’ve seen the future, might have answered that question like this:

“I’ll deliver the Long Island Press, stock shelves at Gimbel’s, wash cars at Thrifty Rent-a-Car, manage a video store, pick up garbage at LaGuardia Airport, proofread self-published books, and work with dumbbells in gyms all across the metropolitan area.”

Paradoxically, I also could’ve said I’d appear in martial arts movies and be on the cover of a karate magazine, would be quoted in the New York Times, sing in a rock band, manage a heavy metal band, have 12 books published, and armed only with a high school diploma would give talks in front of many thousands of people — including at MIT and Yale.

There is no template, I told them, no formula for carving out an artistic and/or activist career in a society such as ours. We live in a free country but that doesn’t mean it’s easy to break free of the cookie-cutter formula.

What feels like freedom is often nothing more than longer chains and bigger cages.

What passes for rebellion is usually co-opted, sanitized, and sold back to us as a trend, a commodity.

The first line of defense against this system of oppression is our own minds.

In a spoken word poem called “My I.Q.,” Ani DiFranco began:

When I was four years old

They tried to test my I.Q.

They showed me a picture

Of 3 oranges and a pear

They said,

Which one is different?

It does not belong

They taught me different is wrong

I reminded those Ivy League counselors that it is artists and activists who prove otherwise. Different is not wrong. Different is essential. It is artists and REAL activists who can help challenge the American Dream myth. You know, the fable of individualized success, e.g. if you just work hard enough and fight your way past the competition, this is the land of opportunity — anything is possible for anyone.

If you succeed, it’s because you deserved it more than others.

This myth is superficially helpful for praising success, but quite damaging in explaining failure. If you “fail,” the blame is on you — with no mention of a system designed in many ways to suppress you.

I say it’s long overdue that we do away with this divisive concept of the American Dream and cultivate new, more realistic American Dreams (plural).

Dreams not for sale to the highest bidder. Dreams not based on material consumption or physical beauty. Dreams that promote and extol unity and collective success while maintaining our individuality and independence. Dreams that challenge humans to think for themselves and about others.

Helen Keller once declared, “Many persons have a wrong idea of what constitutes true happiness. It is not attained through self-gratification but through fidelity to a worthy purpose.”

In that spirit, I closed my Yale talk with a challenge to my audience: “Here’s to all of you, whose ‘worthy purpose’ it is to help others find theirs.”

Highly contemplative.

I cherry picked this: What passes for rebellion is usually co-opted, sanitized, and sold back to us as a trend, a commodity.

Nothing to be sold to people who haven't access to their money, and those who don't need it, don't you know...

Loved this! Very insightful. It’s such a shame that society ranks and measures, & that children are brought up this way. It’s hard to escape. A strong value of mine is constant, relentless, nurturing, & supportive parenting. Reinforcing values that matter. I started morning conversations when my kids were toddlers, brainstorming about “who can I be kind to today?” And, always, after the first day of school each year, “tell me about how you welcomed the new kids”.

My kids are 26 & 28 now and we laugh that perhaps some of my parenting techniques arose as trauma responses. ( Little do they know!) 😉

Both of my kids live in large cities in the NE US. They have what would be considered impressive jobs with big responsibilities. And yet our conversations often still center around times they have been thoughtful, helpful, or supportive of others. For example, my daughter recently saw a teenager in a wheelchair get off the bus (NYC) by himself and appeared to be struggling with navigating the sidewalk & traffic. She approached him and offered to help as it started to rain. He accepted as she popped an umbrella over them. Turns out he was starting a new school, traveled in from NJ, via 2 busses/trains. He said he had miscalculated the commute, as he’d already spent over an hour en route & he was late. She said she was heading right to his destination anyway (lying can be appropriate). She got him to the front gate & offered to get him to a classroom but he preferred to enter solo & she appreciated that.

She told me about it on the phone, after work, as she was simply recounting her day. It was more of a hey, I got caught in the rain this morning story. No big deal.

I secretly cheered as she hit a two-fer... being helpful AND being a positive part of someone’s first day at a new school!

I’m not sharing all of this to virtue signal (I don’t even know you guys!), but to perhaps inspire someone to make today a better day for someone, and especially a kid.