Happy Cesar Chavez Day!

(and don’t forget Dolores Huerta)

“The fight is never about grapes or lettuce. It is always about people.” (Cesar Chavez)

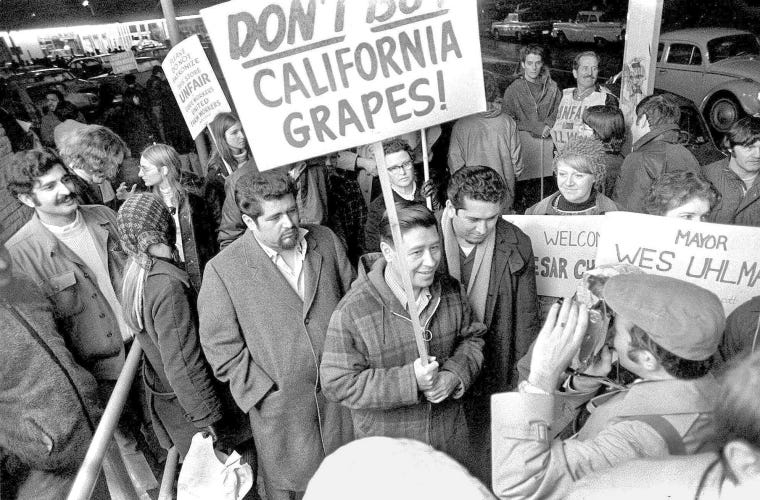

In the late 1960s, thanks to Cesar Chavez and the United Farm Workers (UFW), deciding whether or not to buy grapes became a political act.

Three years after its establishment in 1962, the UFW struck against grape growers around Delano, California — a long, bitter, and frustrating struggle that appeared impossible to resolve until Chavez promoted the idea of a national boycott.

Trusting in the average person's ability to connect with those in need, Chavez and the UFW brought their plight — and a lesson in social reality — into homes from coast to coast. And Americans responded.

"By 1970, the grape boycott was an unqualified success," writes journalist Marc Grossman. "Bowing to pressure from the boycott, grape growers at long last signed union contracts, granting workers human dignity and a more livable wage."

Chavez is perhaps best known for the grape boycott, but he was always the first to admit that it was not entirely his idea. In fact, he was initially against the boycott until his co-workers explained that the best method was not to boycott individual labels, but all grapes. In this way, the grapes became the label itself.

Side note: History so often tells us the lie that singular (male) heroes emerge fully formed in moments of crisis. In reality, success is achieved slowly through collective effort. Cesar Chavez, of course, did not work alone. For example, the incredible Dolores Huerta (photo above) played a crucial role and still does so today. I was fortunate to briefly meet Dolores in 2017 at a screening of a documentary about her life.

But now, back to Cesar on his big day…

Through hunger strikes, imprisonment, abject poverty for himself and his large family, racist and corrupt judges, exposure to dangerous pesticides, and even assassination plots, Chavez remained true to the cause and to the non-violent methods he espoused. Even when threatened with physical harm, the furthest Chavez and his comrades would go is deterrence.

Case in point: Once in 1966, when Teamster goons began to rough up Chavez's picketers, a bit of labor solidarity solved the problem without violence. William Kircher, the AFL-CIO director of organization, called Paul Hall, president of the International Seafarers Union.

"Within hours," writes David Goodwin in Cesar Chavez: Hope for the People, "Hall sent a carload of the biggest sailors that had ever put to sea to march with the strikers on the picket lines. There followed afterward no further physical harassment."

"The fight for equality must be fought on many fronts — in urban slums, in the sweatshops of the factories and fields," said Martin Luther King, Jr., in a telegram to Chavez after a UFW electoral victory. "Our separate struggles are really one — a struggle for freedom, for dignity, and for humanity."

The roots of Chavez's effectiveness lay in his ability to connect on a human level.

"He never owned a house," wrote Grossman. "He never earned more than $6,000 a year. Yet more than 40,000 people marched behind the plain pine casket at his funeral, honoring the more than 40 years he spent struggling to improve the lives of farm workers."

Chavez was once asked: "What accounts for all the affection and respect so many farm workers show you in public?"

He replied: "The feeling is mutual."

Thank you for the very interesting history lesson , Mickey. Never knew about Dolores.

And what a telling quote from Cesar Chavez.

I'm embarrassed to admit I know so little about history. Thank you for bringing these interesting and important nuggets to us. It finally occurred to me a while back that our "education" system DELIBERATELTY makes history boring, disjointed and seemingly irrelevant to our lives BY DESIGN. True history is far from boring; it's fascinating! They try to make history irrelevant and confusing, so we never delve deeper into it and develop a true understanding. As they always say, "knowledge is power" and they try to disarm us whenever they can.