What a forgotten 2014 documentary can teach us about "sex" trafficking & missing children

(an interview I did 7.5 years ago)

In late 2015, I interviewed two filmmaker friends who had completed (in 2014) a must-watch documentary about child trafficking called Who Took Johnny.

The written interview went live in January 2016. In light of recent discussions, I’m re-sharing now it to add some context to today’s so-called debate.

Reminder: This crisis did not begin with QAnon, Epstein Island, or the madness of Trump being called “the new Moses.”

Below is my interview with some very minor edits.

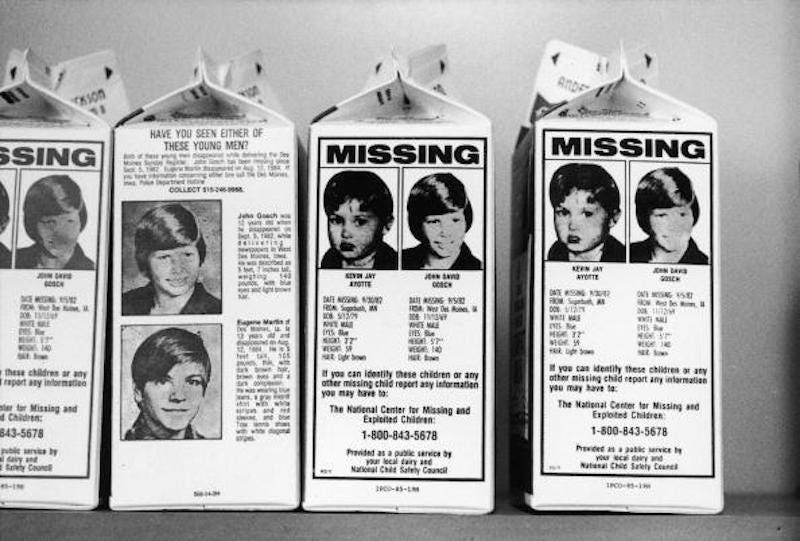

From the Who Took Johnny press kit (2015):

There are currently almost 90,000 unsolved missing person cases in the Department of Justice database, and it's clear that even with all of the advancements in technology and public awareness, the problem of missing and exploited children has only gotten worse since Johnny disappeared over 30 years ago. Understandably with such an ugly issue, people would rather skip over reading about these stories or change the channel of a news report, pretending the problem doesn't exist, rather than confront the brutality of the exploitation and trafficking of children in our country.

I met Michael Galinsky and Suki Hawley somewhere around 1999 when they were making a documentary about Sander Hicks and Soft Skull Press. Hicks was about to publish my first book, Saving Private Power: The Hidden History of “The Good War,” hence it was inevitable we’d all cross paths. We did, we hit it off, and we stayed in touch — zig-zagging across the realms of NYC art and activism.

Teaming with their partner, David Beilinson, Suki and Michael formed Rumur and together have created an array of essential, must-see documentaries, e.g. Battle for Brooklyn, Code 33, and Horns and Halos.

Their most recent film, Who Took Johnny, led us yet again to land on common ground. It centers on the oft-hidden/ignored plague of pedophilia, child abuse, and “sex” trafficking, topics on which I’ve been writing.

Michael saw one of my recent articles, set me up to see Who Took Johnny, and this interview became inevitable.

Mickey Z.: I’ve always been moved by your work. For example, I wept through the last 30 minutes of Battle for Brooklyn. However, Who Took Johnny is straight-up haunting me. So, firstly, how did you get involved in this project?

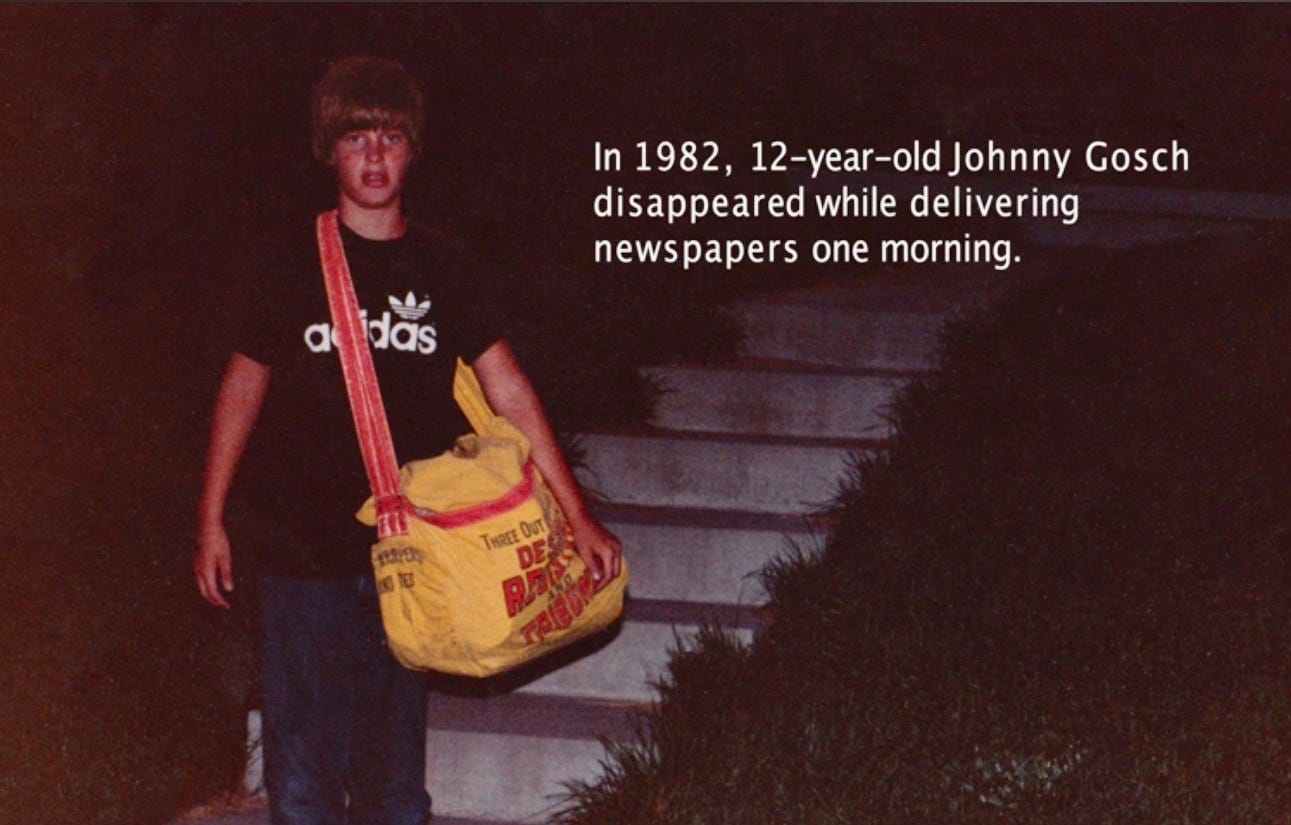

Michael Galinsky: After a screening of Horns and Halos, a guy named Nick Bryant approached us and said, “I've got a story for you.” He proceeded to tell us all about the Franklin Scandal. He was writing a book about this insane story of children being trafficked, blackmail photography, bribery, and nefarious political shenanigans. We started to make a film about his efforts to tell this story, but it was just too big and there was no way we could get it funded. We tried, but we failed. We thought that the Johnny Gosch story, which was really just a small sideline to this bigger scandal, was a story that could be told as a film. It took another few years of trying but we finally got MSNBC to pay for a short TV version that allowed us to shoot the whole thing. Still, we were nervous about trying to make it.

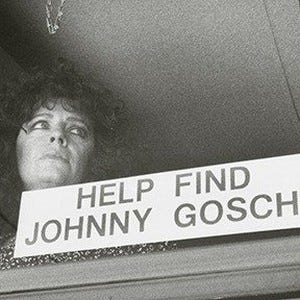

Suki Hawley: The Franklin Scandal was horrendous but didn't have any major characters we could follow and empathize with — and up to then, that's the kind of film we were interested in making. The Johnny Gosch story had more empathetic characters and a really good one: a mother searching everywhere for her lost son but nobody would listen to her. MSNBC agreed to make a version for TV broadcast but also agreed to leave us the rights to make a feature documentary, which is what Who Took Johnny became.

MZ: I’ve researched and written about such issues but so much of this film floored me and/or took me by surprise, e.g. the lifetime dedication of Noreen (Johnny’s mother), the scope of this problem, how impossible it feels to address it when those in power will not step up or are perhaps involved. How about you? What surprised you? Where did Who Took Johnny lead you that you never expected to go?

SH: The whole thing was surprising and difficult to deal with, which is why it took us so long to make the film. I went through the same kind of reactions to the story that seems to happen culturally: first aversion and avoidance of dealing with the details of the story, then slowly coming to hear more and more that makes sense and is hard to deny. At that point, the passion for justice takes over because you can see Noreen's theories have merit and yet everyone is acting as if she's a crazy person. Upon seeing that no one was listening to her, it became important for us to at least give her a chance to speak and lay out her ideas on the events of the early '80s. The film never takes sides but presents what Noreen has to say, intercut with the other known evidence that exists (which tends to corroborate her theories). And the idea was if the film gained enough of an audience, then law enforcement would have to react to the information and explain why they did or didn't agree with Noreen's version of the events. That hasn't happened yet.

MG: It all surprised us at first, but then we started to see the patterns that were discussed. We would see the stories about pedophile stings and child porn stings where people were rarely named and nothing really came of them. The Johnny story was a lot less scary than the Franklin story because that was much more organized and much deeper. I think the hardest thing about the film was going with Noreen to shoot with the Collins family who were struggling to deal with the disappearance of their daughter. I don't think I have ever been as emotionally overwhelmed as I was in that situation.

SH: I, too, was floored by Noreen's commitment and dedication to the thankless job of finding out what happened to her son. In working on this film, it became obvious that most parents can't function when this type of thing happens and they rely entirely on law enforcement to carry out the investigation. The fact that she had the tenacity to dig into this so deeply on her son's behalf while being actively deterred by law enforcement, was incredibly unexpected.

MZ: Through my writing, I've learned firsthand how defensive people get (usually men) when confronted with the word that their heroes are exploiters of children, pedophiles, or pedo-apologists, e.g. Burroughs, Ginsberg, Jimmy Page, R. Kelly, Gore Vidal, Roman Polanski, Bowie, etc. Have you encountered anything similar and if so, can you share examples and/or any insights on the root of this dangerous reality?

SH: The idea of pedophilia is so abhorrent in our culture that most people say, “ick,” and turn away, so as not to have to deal with it. But as Paul Sparrow says in the film, it exists in a way that shouldn't be ignored. I think the biggest way this is manifested is in the news stories when law enforcement does a big pedophile “sting” around the Super Bowl, where they “round up” a group of 20-30 men, and haul them off somewhere. It's always an anonymous group, who are dealt with and whisked away so we don't have to think about that anymore. Since working on this film, I've read the stories like this over and over, stories we usually avoid so we never notice how stunningly similar they are. There's never a follow-up identifying any of the suspects, and we never know exactly what happened. As soon as our culture can come to deal with this in an emotionally mature way, the whole thing will be able to be examined honestly and understood in the arena of complexities where it exists.

MZ: Your film offers a frightening, much-needed reality check on such abuse. These nefarious predators go out of their way to abduct children from close-knit families in order to maximize the emotional pain and if such a child attempts to escape, they are literally branded. As I said earlier, I am haunted by what I learned from Who Took Johnny. Have you heard from other victims, other families, or anyone else seeking ways to help end this scourge?

MG: The film has not really made it into the world so, no, we haven't heard from anyone else — it simply hasn't been seen in a way that could make that happen.

The fact that Who Took Johnny has not yet attained notoriety dramatically highlights the drastic need for more independent and socially aware filmmakers to reach more hearts and minds. Rumur’s work deserves a wide audience and our society desperately needs alternatives to the vapid, culture-reinforcing Hollywood spectacles. Learn more about Who Took Johnny here. Spread the word.

Most importantly, I hope this interview has helped shine a light on the brutal and omnipresent reality of child exploitation and pedophile culture. Saying “ick” and then refusing to talk about it in polite society only enables this plague and its predators. If you feel jolted and angry about this issue: speak up, get involved, and fight back! Ask yourself: how can I help and how soon will I begin?

(For starters, please report child exploitation here.)

Coda (2023): The Franklin Scandal was exposed almost 35 years ago. Johnny Gosch vanished more than 40 years ago.

Again, well before QAnon and Epstein, this problem has been around for a long, long time and transcends distractions like political parties or a new trendy movement [sic].

Imagine if instead of endless scrolling and flame wars, we embraced intellectual independence and spiritual awareness. I’d call that an important step in a better direction.

A long time ago in Belgium there were the pink ballets, a circle of child porn, abuse, and worse. Who were involved - the creme de la creme in Belgium. The brother of king Boudewijn, later king Albert, father of the present king, former prime minister Vanden Boeynants, and several other high - ups. A girl who had been able to escape described in detail the room where a dead girl, obviously tortured, sacrificed, was found. She had recently married and her husband had urged her to come forward. Both the girl and the officer who interviewed her were bashed, the officer lost his job and the girl was painted as a lunatic, even though she could describe the tortures, the inside of the room and the people present. A few details, probably due to furniture moved etc. made her 'unbelievable'. One of the kidnappers of Vanden Boeynants was arrested in South America and returned to Belgium, and found hung from his heating in his cell. The heating was sitting under the window sill. Try hanging yourself from that. The royal house in Belgium, as all others in Europe, is closely connected to WEF (all from german origin through queen Victoria) and all groomed by them

Thank You Mick.

& Guests.

Really Good Piece.